Transnistria: Captured Moment with Lenin Statue

Journey to the Realm of the Past: Exploring Transnistria

A stern voice rings out, echoing through the cluttered border post. "Passport, please." The woman, adorned in a moss-green uniform, sports pink hair and a leopard print nail polish. The country we're entering is not officially recognized, yet it stands its ground. Armed soldiers, some barely older than teenagers, keep a watchful eye from every corner. The red, green, red flag with a hammer and sickle flutters above. Welcome to Transnistria, or as some call it, Pridnestrovie.

Just an hour ago, we were in the sprawling market of Chisinau, Moldova's capital, surrounded by bustling vendors, gold-toothed women carrying heavy bags, and tinny Russian pop blaring from speakers. A shared taxi, or marshrutka, stood ready for the 80-kilometer journey to Tiraspol, Transnistria's capital. The driver nodded towards the minibus, "Tiraspol's over there." The fare? About three euros.

Buzzing pop music and a vanilla-scented air freshener filled the minibus, while the driver's saintly gazefrom the vehicle's wall was our constant companion. The journey took us past Moldova's high-rise blocks, leaving them behind as we ventured deeper into Transnistria.

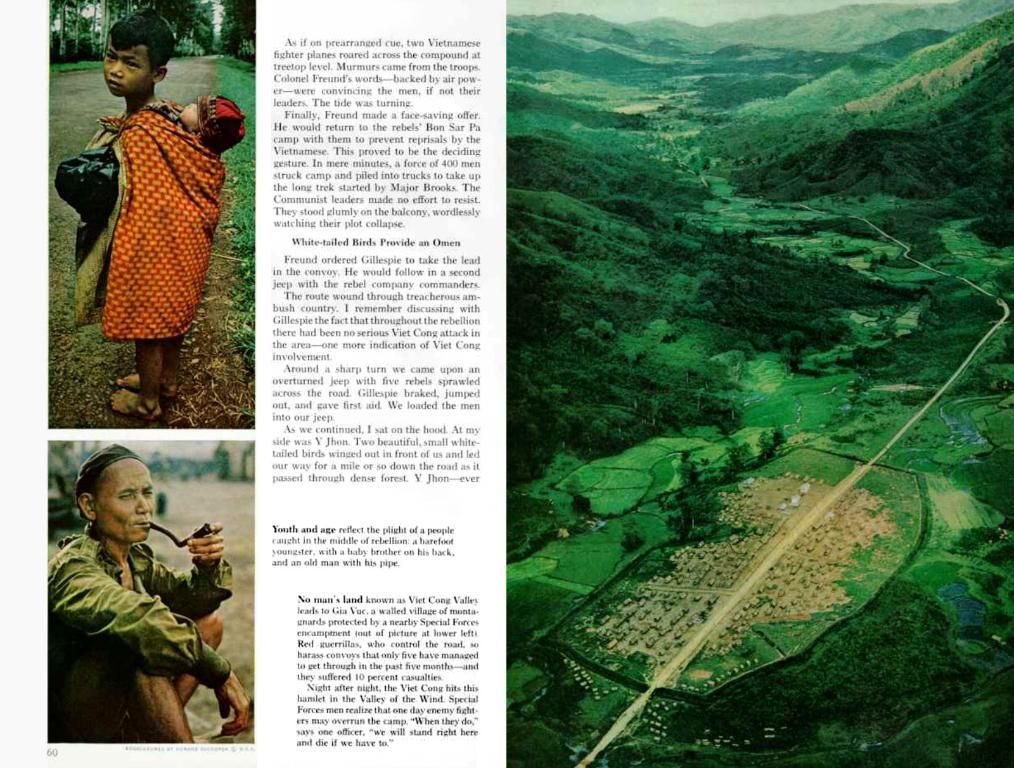

This 200-kilometer stretch of land along the Dniester River feels like a time capsule, brimming with the charm of yesteryear. Its capital, Tiraspol, is a striking blend of Soviet legacy and modern-day Eastern Europe. Monumental government buildings, Lenin and Gagarin statues, and red-painted playgrounds dot the landscape, while Soviet posters adorn school doors, harking back to the Great Patriotic War.

But Transnistria is more than just a living museum; it's the last outpost of the Soviet Union in Europe. The region relies heavily on Russian financial and military support, which often fuels tension between the EU and Russia. Half a million people call Transnistria home, and many carry three passports: one from Transnistria, one from Moldova, and one from Russia.

Just before reaching Tiraspol, a striking spectacle emerges: The Sheriff Tiraspol sports complex, home to the record holder of Moldova's football. The team boasts an impressive roster of foreign professionals, thanks to significant financial support from the Sheriff conglomerate. The namesake sponsor is an omnipresent force in Transnistria's economy, owning television and radio stations, liquor factories, supermarkets, and gas stations. Some speak of a "Sheriff oligarchy."

During our visit, an elderly woman with fiery red hair crosses herself at every church the minibus passed, while soldiers stood silently at checkpoints, their faces betrayed no emotion. Tourist groups embark on guided tours, led by locals like Anton, who boast an American accent and an endless supply of jokes. The Englishmen we met, looking for a piece of the last remnants of the Soviet Union, bought a few refrigerator magnets from Anton.

While some are drawn to Transnistria for its unique historical and cultural appeal, others shun it due to its troublesome political situation and poor reputation. Cautionary tales of robberies and kidnappings swirl in travel forums, and Germany advises against visiting due to the unstable political climate, particularly due to the ongoing war in neighboring Ukraine. Yet, the city is not as threatening as some make it out to be. Tiraspol is relatively tranquil and offers a friendly, if somewhat reserved, welcome to its visitors.

Experiencing Transnistria is like stepping back in time. Landmarks from the Soviet era are abundant, offering a captivating glimpse into the past. But the signs of the Soviet Union's collapse are also evident, with old Ladas sharing the roads with foreign luxury cars, and new structures inspired by Gulf states' architecture, rather than Soviet design. Our tour concluded at "Back in the USSR" restaurant, where we savored traditional dishes like borscht, shashlik, and pelmeni in an atmosphere that was equal parts kitschy and nostalgic.

Leaving Transnistria wasn't without its unique touch. As we crossed back into Moldova, a soldier collected our passports and migration papers, glancing at them for just a moment before returning them. The journey back to the present felt momentous, yet bittersweet, as the allure of Transnistria's enigmatic charm lingered long after we left.

Travel Tips:- Visa-free entry for German passport holders lasts up to 90 days when visiting Moldova.- Fly directly to Chisinau from Germany via Eurowings, Lufthansa, LOT Polish Airlines, Austrian Airlines, or Fly One.- Continue your journey to Transnistria by shared taxi or bus.

In the realm of Transnistria, travelers can delve into the mystique of a Soviet relic, immersed in its unique lifestyle and political context. While exploring historical landmarks, one may find themselves engaged in conversations about general news, such as the region's dependence on Russian support and its fluctuating relationship with the EU. As we savor traditional dishes at "Back in the USSR" restaurant, we unwind with regional pop music, offering a though-provoking blend of old and new, politics and travel.